Am I Your Pastor or Your Priest? It Depends Who’s Asking.

Clergy titles—preacher, pastor, minister, and priest—reflect distinct expectations: proclaiming, caring, organizing, and mediating the sacred. Each shapes how congregations understand ministry. My own draw toward the priestly role reveals how unfamiliar titles spark curiosity. What we call clergy forms both their identity and the community’s expectations.

It is not uncommon for clergy to be called different titles. These titles might reflect the tradition the speaker comes from, and that tradition might have a preferred role for a clergy person. The four most common titles I have been given in this way are:

Preacher

Pastor

Minister

Priest

Perhaps used interchangeably, these titles really are four different ways of being a clergy person.

The title preacher places unmistakable emphasis on the act of sermonizing. One of the clearest examples of the expectations woven into this title comes from a greeting I have received more than once: “Hey preacher, what’s the Word for today?” Whether I am standing in a pulpit or waiting in line at the pharmacy, the assumption is the same—the clergy person’s primary role is to preach.

I have walked into hospital rooms and been met with, “What are you doing here, preacher?” This is often said as a way for the patient to acknowledge that their condition may be more serious than they realized, or perhaps to apologize for inconveniencing the clergy person. But it also reveals another assumption: if someone understands the clergy person primarily as a preacher, then it feels strange to see that person in a hospital room. Hospital visits, after all, belong to the domain of the pastor, not the preacher.

The title pastor places the emphasis on care. I never took any courses in “preacher care,” but I took several in “pastoral care.” Because the pastoral identity carries a premium on caregiving, pastors often spend less time refining the art of preaching and more time developing their relational skills. During my internship, a pastor once said to me about preaching, “The congregation doesn’t care what you know until they know that you care.” One of the most iconic pastors I know is a man named Raul. Raul was not a strong preacher and was often late to events, yet he was given endless grace because everyone knew that Pastor Raul’s heart was consistently oriented toward serving others.

If the title pastor emphasizes relationships and individual care, the title minister tends to emphasize relationships and communal care. Ministers often give greater attention to structures, systems, and organizational dynamics because the scope of their responsibilities extends beyond what a single person can accomplish alone. There is likely a reason the words minister and administer share the same root. When I arrive at weddings I’m officiating, the coordinator usually asks, “Are you the minister?” The State recognizes clergy as administrators on its behalf. In addition, ministers are often expected to supervise others or manage systems in ways that preachers and pastors are not. In particular, the minister is presumed to have a stronger role in the temporal management of the church or congregation.

The title priest also emphasizes management, but it is aimed less at managing the temporal realm and more at stewarding the spiritual realm. The role of the priest is that of a mediator between earth and heaven. In many traditions, particularly within Catholicism, priests administer sacraments that are not understood in purely material terms. The sacraments are sacred, imbued with or transformed into something transcendent. In the priest’s hands, bread and wine become the body and blood; water becomes holy water; a simple bedside prayer becomes a rite for the dying; oil becomes Chrism. Of the four titles, priest is the one I have been called the least, yet people have asked me to fulfill priestly functions more times than I can count.

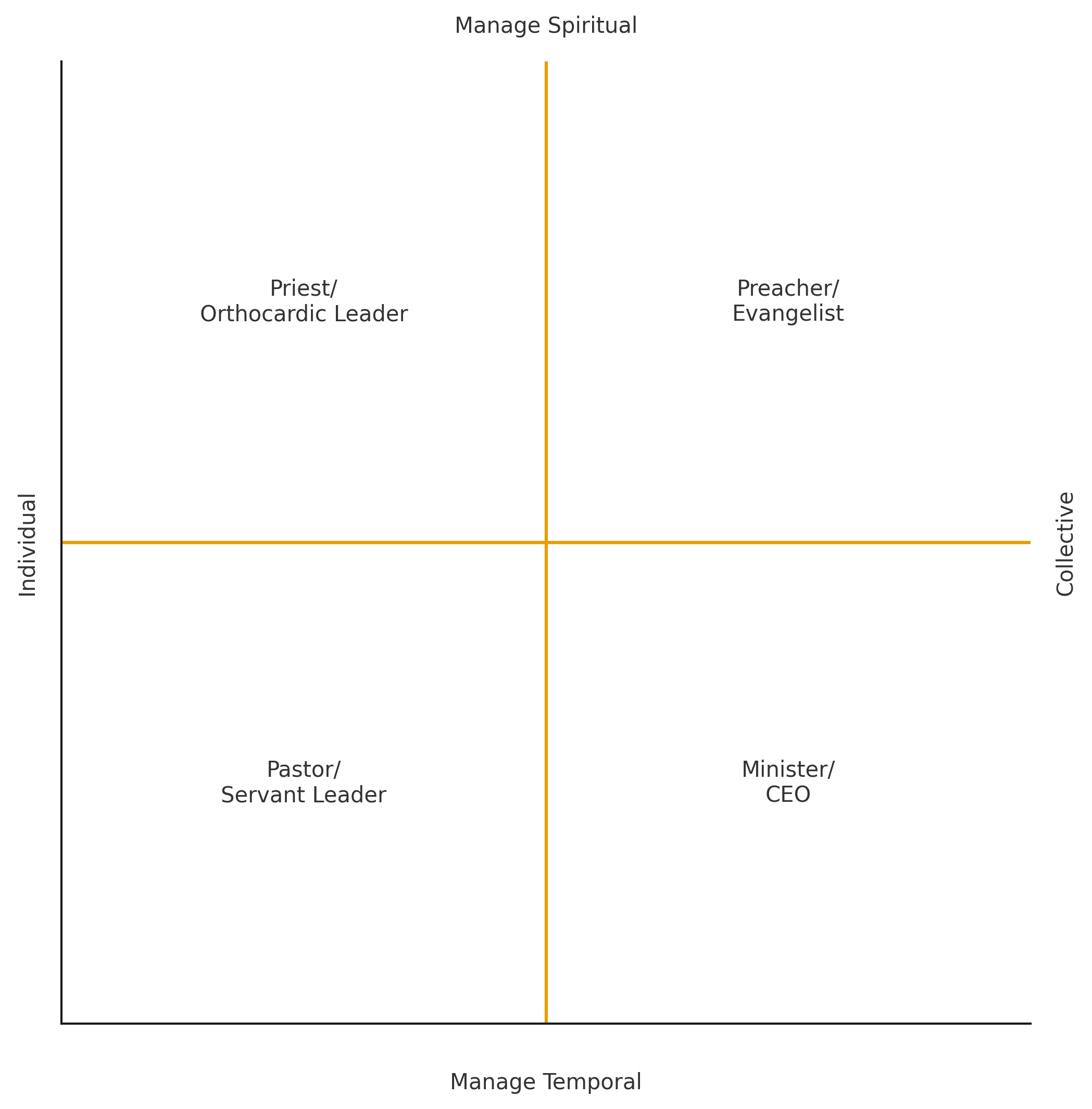

If we were to chart these four roles, we might picture a vertical axis distinguishing different forms of management and a horizontal axis highlighting whether the emphasis is on the individual or the collective. (Readers of Orthocardic Leadership – Pastoral Leadership Inspired by Desert Spirituality will also recognize how the four models—Orthocardic, Evangelist, Servant Leader, and CEO—fit naturally within this same matrix.)

In my local church, every clergy person is called “Pastor _________.” This is not because any of us requested the title—certainly not in my case as “Pastor Jason.” Rather, it reflects an embedded theological assumption within the congregation. In this community, the implicit expectation of clergy becomes explicit the moment someone names us.

Personally, I am drawn toward the role of the priest. Whenever I talk about Orthocardic Leadership in my tradition, the immediate response is usually, “I love the idea—but what does it look like?” My struggle to articulate it is partly a reflection of my own tradition’s limited experience with priests. Yet I have learned something surprising: the more I function in priestly ways, the more people express curiosity about ministry, religion, and Christianity itself.

What role or title do you implicitly associate with clergy? What we call clergy, and what clergy hope to be called, is never just a matter of preference. It is language that shapes both the clergy person and the congregation.

Why Seeing God’s Face Could Kill You

Exodus 33:18-20 (NRSV) reads:

18 Moses said, “Please show me your glory.”

19 And he said, “I will make all my goodness pass before you and will proclaim before you the name, ‘The Lord,’ and I will be gracious to whom I will be gracious and will show mercy on whom I will show mercy.”

20 But,” he said, “you cannot see my face, for no one shall see me and live.”

This raises a question: why would someone die if they looked at God’s face? The issue seems especially puzzling because just a few verses earlier in chapter 33, we read:

11 Thus the Lord used to speak to Moses face to face, as one speaks to a friend. Then he would return to the camp, but his young assistant, Joshua son of Nun, would not leave the tent.

One explanation is the scholarly idea that the Hebrew Bible has multiple authors over time, with editors weaving together different traditions into the story we read today. Verse 11 might have been written by a different author, in a different place or time, than verse 18. While this explains the apparent contradiction, it doesn’t fully inspire or shape the hearts of those who read the Bible. Interpretation is about inspiration, not just explanation.

Let us consider another perspective: perhaps the danger in seeing God’s face is less about God and more about Moses—or, more broadly, about us.

When we look someone in the face, we inevitably see ourselves reflected in their eyes—not just metaphorically, but literally. And if you’re like me, seeing yourself in a mirror often triggers harsh judgment:

“You look old and tired. You should eat better. Your hair is thinning, your face has changed, and that shirt doesn’t fit. If others really knew you, they’d reject you.”

We internalize rejection as a “fact.” We resist accepting that we are accepted—by the world, and even by God—because we are conditioned to believe we are worthy only of rejection.

Perhaps when God says, “You cannot see my face, for no one shall see me and live,” it is because the danger lies not in God’s face, but in our own self-condemnation. To look directly at God is to see our reflection in God’s eyes, and if we cannot yet receive love, we might judge ourselves so harshly that it leads to self-harm. It is not God who kills us; it is our own fear and rejection of God’s acceptance.

Moses, however, models another way. He shows what it might be like to move from accepting rejection to accepting acceptance. At times, Moses is able to be face-to-face with God—but in those moments, he does not see himself in God’s eyes. Instead, he sees himself through God’s eyes. Moses perceives himself as God sees him: beloved, beautiful, and fully accepted. When he can see himself through God’s eyes, Moses stands face-to-face with Love itself.

Beyond Inclusive and Exclusive: Rethinking Church Boundaries

This article challenges the simple divide between inclusive and exclusive churches, proposing four types of communities based on how they welcome or reject others and how they handle exclusion itself.

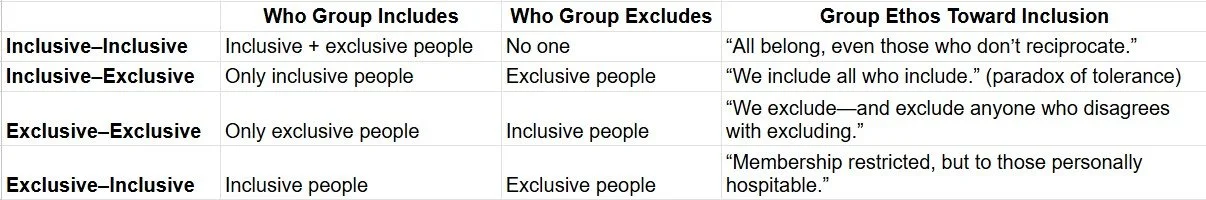

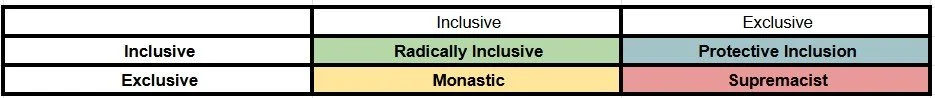

Over the past months, I have kept coming back to the words inclusive and exclusive, and specifically how these words are used to describe churches. It is too simplistic to say that some churches are inclusive and others are exclusive. Rather, it is worth considering the combinations of inclusive and exclusive. Placing them in a matrix, you get this.

From there, it is just a matter of fleshing out these combinations.

The Inclusive-Inclusive box. Because this group’s orientation is hospitable toward everyone, regardless of how they treat others, the group includes both inclusive people and exclusive people. This is the group or church that welcomes everyone - including the prejudiced and intolerant, on the understanding that hospitality does not depend on reciprocal action. This group is characterized by:

Unconditional hospitality

Exclusion itself is not grounds for exclusion

Emphasizes grace, openness, universality

We might call this box “Radically inclusive,” “Unconditional Welcome Group,” or “Universalist Community.”

The Inclusive-Exclusive box. This group includes inclusive people, but excludes exclusive people. Put another way, this group includes everyone, except those who refuse to include others. This is a concept sometimes referred to as the paradox of inclusion, which I encountered when Peter Rollins introduced me to Russell’s Paradox. You can read more of the inclusion paradox here. Still, the gist is that radical openness cannot survive if it refuses to set boundaries against forces that undermine openness itself. This group is characterized by:

Open to all except those who undermine openness

Inclusion is itself a moral boundary

Reflects the "paradox of tolerance"

We might call this box “Protective Inclusion Community,” “Boundary-of-Belonging Group,” or “Conditional Inclusion Community.”

The Exclusive-Exclusive box. This group is composed of people who exclude others, and the group also excludes inclusive people, because they do not share the group’s exclusionary values. Put another way, this group excludes others, and also excludes anyone who does not want to exclude others. For example, a white supremacist group excludes non-whites, but also expels members who object to the exclusionary project. This group is characterized by:

Identity protection or separation

Requires ideological conformity

Excludes both outsiders and dissenters within

We might call this box "Purity-Based Community,” “Closed Tribal Group,” or “Supremacist Community.”

The Exclusive–Inclusive box. This group sounds like the most complicated, but it seeks to exclude others generally. However, this group paradoxically includes people who are inclusive and excludes those who are exclusionary. To put it another way, membership is limited, but the members themselves are welcoming. As complicated as that may sound, think of the example of a private club or a monastery. Both of these groups screen applicants for specific interests (thus, the group has exclusive membership), but the group admits only those who themselves are socially welcoming and non-discriminatory. This group is characterized by:

The boundary is exclusive (not everyone permitted)

Those who belong are personally inclusive

Separateness without hostility

We might call this box “Selective but Hospitable Community,” “Covenantal Group,” or “Monastic Community.”

To summarize:

Or if we want to label the original matrix, we might get this:

This simple taxonomy of groups is helpful to help us define what type of group we are trying to create. Some of us in the UMC see the “radically inclusive group“ as the goal. Some in the UMC see that a “radically inclusive group” has a self-destructive feature embedded within it, and seek the goal of a “protective inclusive group”. The astute thinker can see there is a fine line between the inclusive-exclusive and the exclusive-inclusive groups. In an effort to create a “protective inclusive group”, the group can self police itself into a “supremacist group”. Likewise, there is a fine line from the “supremacist group” to the “monastic group” as the latter must hold firm to an internal check of filtering people in advance.

If we are going to be inclusive, then we have to deal with exclusion and its place. This paradox, this contradiction, this mystery is not only noble and beautiful, but it is the work of the Church.

Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.