Giving: A Brief Taxonomy

For a bit of time now I have been wrestling with the differences between a gift, a tithe, an offering and a sacrifice. I identify more as a practical theologian than a philosopher and so please forgive if this small taxonomy is reductionist or too simple by academic standards. The goal is to examine the differences in these four ways of giving so it might nudge us to examine our giving - especially in the “season of giving”.

To state an easy point: There are three components of giving - giver, object, and receiver.

To state a slightly more complex point: There are two elements in giving, 1) a desire to control a response and 2) control of the object.

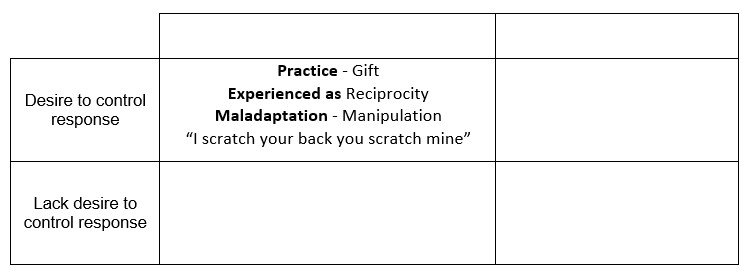

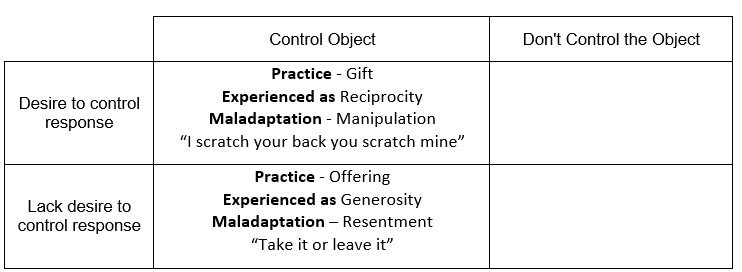

If we put the first element on a matrix it might look like this:

Now, if the giver desires to control the receiver’s response, this type of giving might be understood in the saying “I’ll scratch your back and you scratch mine.” The giver gives with the hope to control the receiver’s actions, such as with words of appreciation or a future object from the receiver. But the goal of the giver is to give an object with the hope to control the receiver’s response. This sort of giving is experienced by the giver and receiver as reciprocity but we identify this sort of giving as “gifting”. We give gifts in order to foster relationships and control the receiver to “give back” in some way. In every act of giving, there is the possibility of a maladaptation and the act of giving is harmful. When the desire to control the response is so powerful that the giver gives to manipulate . Adding to our matrix we get this:

Of course the giver does not always desire to control the receiver’s response. For instance, when we give something with an invitation to “take it or leave it”. The giver is not offended if the object is taken or if the object is rejected. This freedom the receiver has to reject is not present in the above "“gift giving”. In fact, it is rude and potentially hurtful to reject gifts, which is captured in the caution to “not look a gift horse in the mouth.” Even the softer forms of rejecting a gift are up for discussion which we see play out in conversations regarding “re-gifting”. If the receiver were free to reject the gift then the practice of “re-gifting” would lack the social taboo. And so this second type of giving cannot be called “gifting” but is called “offering.” The giver offers the object without a desire to control the receiver’s response. That is why an offering is always experienced as generous, not because of the value of the object but because of what the object lacks. An offering lacks the desire to control that is present in gifting. Many times humans are taken aback by generosity and/or are made uncomfortable by it and the receiver will want to give something in return. Ironically the receiver can cheapen the generous act by reciprocating the gift (which may be why many people give anonymously to different causes). Perhaps the more insidious maladaptation that can develop in an offering is resentment. For instance, when the giver makes multiple offers over time and no one “takes up the offer” the giver might grow resentful towards others and begin to feel like what they have to offer is worthless. One could say that when we grow resentful in our offering, we are no longer giving an offering but moving into gifting. But for the purposes of simplicity, here is offering represented in the matrix:

The first element of giving considers if the giver desires to control the receiver’s response.

The second element of giving considers if the giver has control over selection of the object.

And so our matrix takes an additional form:

In both gifting and offering the giver is choosing what the object is. From a birthday present (gift) to an offer of services (offering) the giver controls the type, amount and frequency of the giving action. However, these are not the only ways to give. There are other ways to give in which the giver does not have much say or control over the object that is to be given. For instance, in the Bible there are a number of laws which dictate the specific object that is to be given. Mary and Joseph were to give to turtledoves as an offering for the consecration of the son, Jesus. In this act of giving, the object was not something that Mary and Joseph chose, it was a directive. Some may call this type of giving as a tax, but for our purposes I am choosing the religious term of “tithe”. The tithe is not limited to the type of object but the specific amount, 10% of the whole. If you are a farmer or a banker, giving a tithe means you are giving a set amount and that amount is prescribed from a “big other”. This “big other” could be god or a government or a parent who died years ago, but giving out of obligation or duty (as the Australian philosopher Peter Singer) is when the giver does not control the object but desires to control the response of the “big other”. It may be to fit in with society, or be seen as faithful, be marked as a law-abiding citizen, or be seen as one who gives, or trying to please God or a parent. Like other forms of giving, this third form of giving can be maladaptive when it is experienced as guilt for failing to give to the standard of the “big other”. Some religious folk often wonder if they are giving enough and many citizens pay their taxes in full so they do not go to bed at night with the guilt of “cheating” on their taxes.

The fourth type of giving is the giving in which the giver not only lacks a desire to control the response but also does not control the object that is being given. This type of giving is perhaps the most radical and it is the sacrifice. If one controls what is being given then there is a comfort in giving. For example, being a care taker of an animal. The giver cannot control all that would be asked of the giver. The animal may get out of the yard while you are at work and you have to go home to fetch the dog. You as the giver did not control when you would give this object of time to the dog, it was demanded of you by a “big other”. The sacrifice not only lacks control of the object given, but the giver also lacks a desire to control the outcome. For instance, no matter how much time a parent gives to a child, the parent cannot control how the child "turns out”. While not limited to the solider, the parent, the guardian, the care taker, the teacher, these are all are arenas where sacrifice is more common.

At the core of Christianity is sacrifice. The first is when God become human. God gave up divinity for humanity and God gave up control how people responded. Another sacrifice of God is on the cross. Here God did not control what was given, that was demanded by Rome. Additionally, God in Christ did not control how people responded at the point of his death and resurrection. At the very core of Christianity is sacrifice and sacrifice has two expressions. The first is what is called “kenosis” which is giving of oneself when it is demanded of you. The maladaptive expression of sacrifice is violence.

There is not a “good” of “bad” type of giving. Each has its place and purpose. What I hope to offer in this short reflection is that what we often call sacrificial giving is more aligned with the “Tithe”. Perhaps those who are great at giving “gifts” are not very good at giving “Offerings”. Maybe our giving is limited in scope and one way we may discover more about ourselves (and God for that matter) is to explore other ways of giving.

The Good News of Re-gifting

Photo by Lina Trochez on Unsplash

Re-gifting has gotten a bad wrap (pun intended) for a while now. I know it is propaganda of the capitalist system that says that you should not give anything to anyone unless you bought it specifically for that person. As though the only possession that is worth giving to someone else are virgin dollars on a new gift. It is silly, but powerful on us. Many of us feel a sense of shame with re-gifting that we would never do it.

The irony is that there is Good News in re-gifting.

Christianity teaches that all things are from God and that humans are stewards of these gifts. We are stewards of money, stewards of natural resources, stewards of animals, and stewards of our sisters and brothers. All that we have is a gift.

As such, anything you give to another is a re-gift. The money you use to buy a “new gift” is a re-gift.

The Good News of re-gifting is that all of life is a gift. And in re-gifting we are reminded of that.

Stop Taking Time

When you attend a clergy session, there is a lot of talk about the need for self care. There are many expressions of self care, but they all are framed the same way. Take time for prayer. Take time to study. Take time to rest. Take time for vacation. Take time for Sabbath.

We are encouraged to "take time" - which I think might be part of the problem.

"Taking time" assumes that time is zero-sum. If we take time from one area (sermon prep) then we will have less time in another area (pastoral care). The idea of "taking time" assumes that if we don't take it then we will never get it - if we don't take time for prayer then prayer will not happen. "Taking time" gives us the impression that if we only were better at taking time then life would be better.

Of course, "taking time" is a metaphor. One cannot literally take time like you can take a cookie from the jar, and when we try to take time, we come up short. Rather than using the metaphor of "taking" time, I would remind you that Christianity offers a different metaphor - receiving time.

Time is a gift that we receive. Time is a gift that we trust will be present when we need it. Time is a gift that we can receive, but we can never take.

When we receive time, time is no longer zero-sum. When we receive time we understand that when we are doing one thing, there will be enough time for other things.

Shifting or metaphor from "taking" to "receiving" is not just semantics, it is a part of our spiritual formation. It is part of the reason I do not take communion.

Be the change by Jason Valendy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.